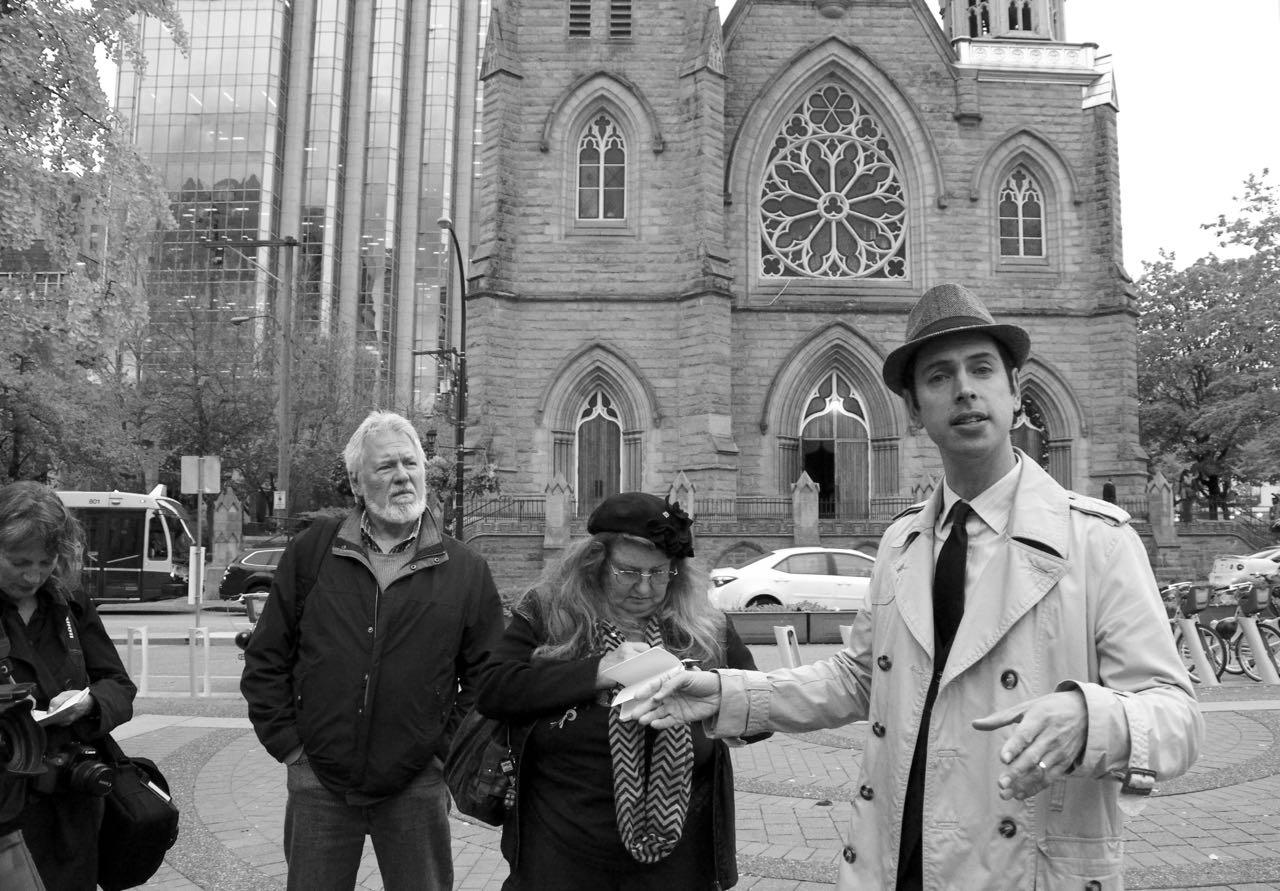

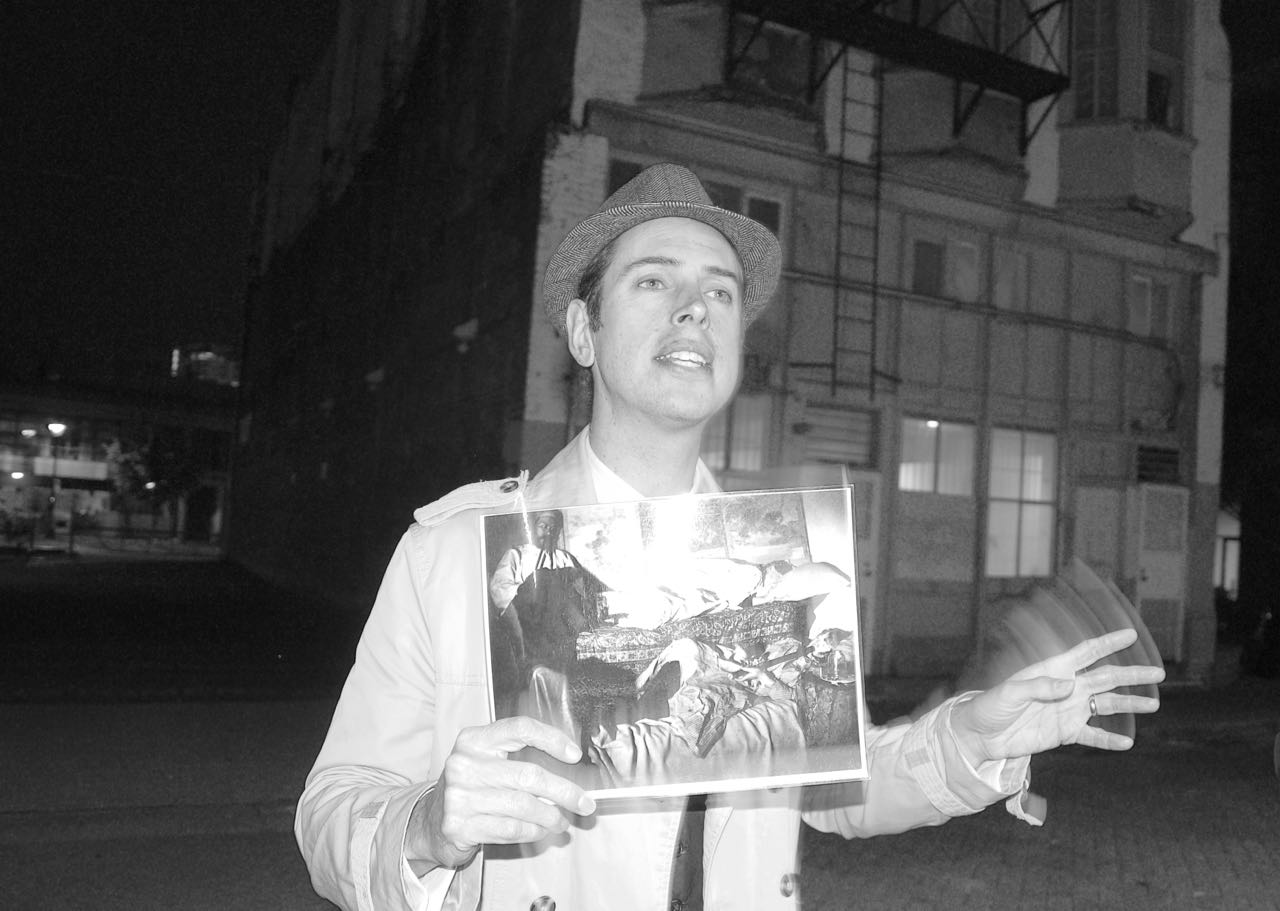

From the grey gloom in the shadow of Holy Rosary Cathedral he emerges, dressed in three piece suit, trench coat and fedora as if stepping from the 1930s. He is Will Woods, founder of Forbidden Vancouver Tours, and our guide for tonight’s walking tour, Prohibition City.

As he speaks, Woods quizzes our group for historical factoids. Correct responders are given Tootsie Rolls as a prize.

He starts by asking, in his East London accent, why our group of travel writers think they were asked to meet him in front of Holy Rosary Cathedral, built in 1898.

“During Prohibition they served more than Holy Communion,” he answers.

Then, we’re off, like a gang of gumshoes, in the direction of Homer and Dunsmuir where we stop to admire the Canada Post building. In the Cold War 1950s, Canada Post built it with a reinforced basement to withstand a nuclear bomb as well as a tunnel to the rail yards that has been seen in TV shows and movies. It must be true, as evidenced by the black and white glossy he pulls from his attaché case.

The 1898-era Victorian Hotel on Homer Street is our next stop. Admiring the style of bay windows and Victorian flourishes, we learned it housed one of Vancouver’s first hotel bars – in the front where the lobby is today.

A stroll down Pender Street leads us to the edge of Victory Square on Hamilton Street where a waft of cannabis smoke evokes a more modern time. We pause to admire the tower of the Woodward building built on the site of the famous retailer, and Woods asks us to sing the jingle for the store.

He points out the Dominion Building, built in 1910 in the Beaux Arts style, the tallest building in the British Empire at the time. Its terra-cotta reliefs showed off the new technology – factory made tiles, churned from a factory in East Vancouver.

At this point I realize this is not just a Prohibition tour of Vancouver, but also an architectural walkabout.

In front of Victory Square’s WWI monument we finally dig into the story of Prohibition in Canada.

The temperance movement was born in 1998 in America’s deep South, he says, over the fear of big city’s influences over county folks, in particular – STDs; young men going to saloons and being tempted by prostitutes who give them syphilis to take home to their wives.

With great fanfare Woods channels the prohibitionists, “We’ll close the saloons and ban liquor and we will save the Canadian family!”

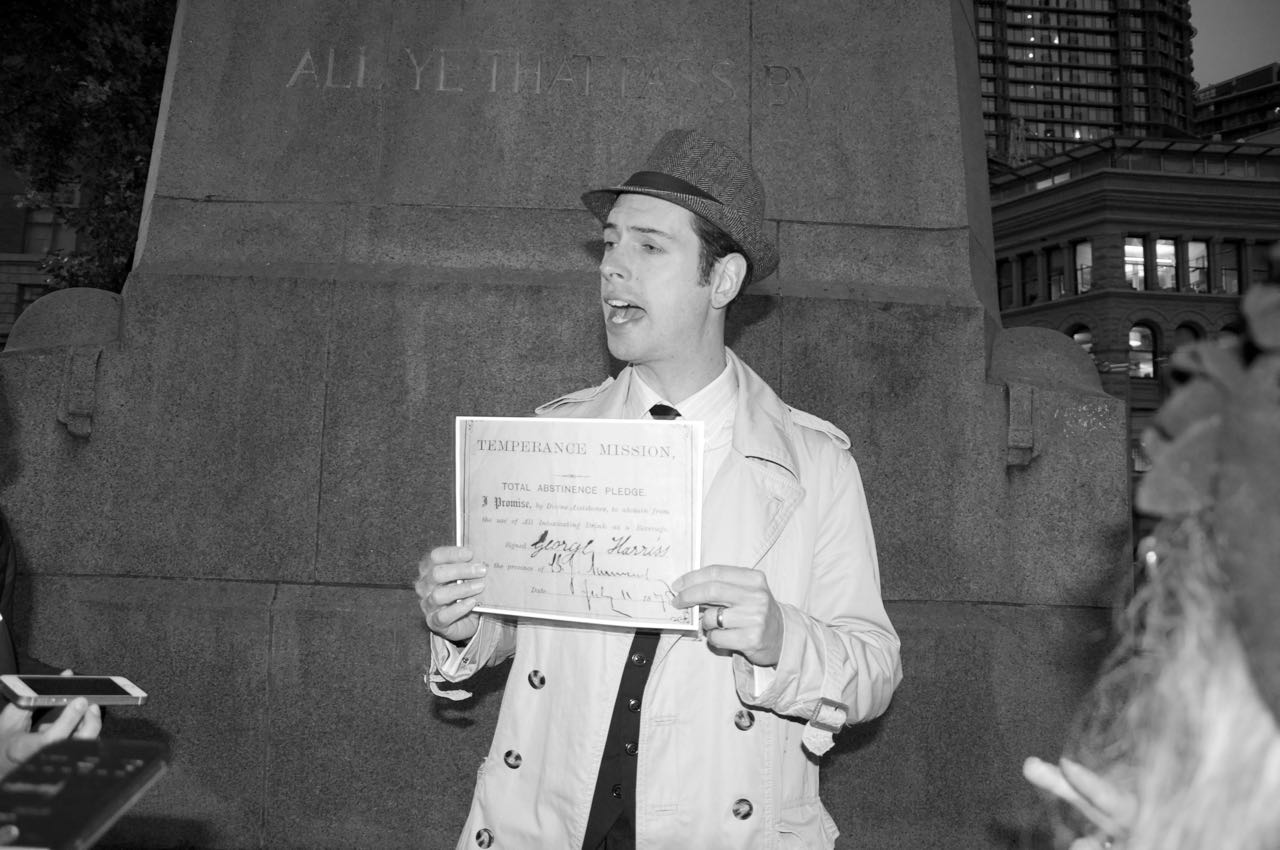

After flashing a copy of the Temperance Mission Abstinence Pledge, and reading a newspaper ad which conflated the war effort with prohibiting liquor, he describes how the BC government put it to a popular vote. In Oct 1916, 36,000 people voted for prohibition with 27,000 against. In 1917, the BC Prohibition Act was enacted and all bars were closed.

After flashing a copy of the Temperance Mission Abstinence Pledge, and reading a newspaper ad which conflated the war effort with prohibiting liquor, he describes how the BC government put it to a popular vote. In Oct 1916, 36,000 people voted for prohibition with 27,000 against. In 1917, the BC Prohibition Act was enacted and all bars were closed.

Again, that smell of Vancouver’s best wafts past us.

In his crisp British accent, Woods continues: “Prohibition is in, saloons closed and it was illegal to manufacture, sell, or distribute, liquor. If you were caught, it was 6-12 months hard labor. Tootsie Roll anyone?”

At that, we are off in search of a “Blind Pig” on the other side of Victory Square off Cambie Street and end up in a very dark ally behind the Vancouver Film School.

Allyways, he says, are some of the best preserved parts of old Vancouver and here the buildings on each side have not changed in 100 years when this area was the center of town.

During prohibition, he tells us, you might have seen one or more blind pigs, “Which was?” We all reply “Speakeasy!” hoping for a Tootsie Roll.

He points out that although “Speakeasy” was not a term used in Canada, a “Blind Pig” was known as a run down, disgusting type of speakeasy located in basements where you knock on the door and someone looks at you through a grate, you give a password, enter down a staircase into a dark room with no window. The liquor served there might have been homemade or turpentine. People went blind and sometimes died of it.

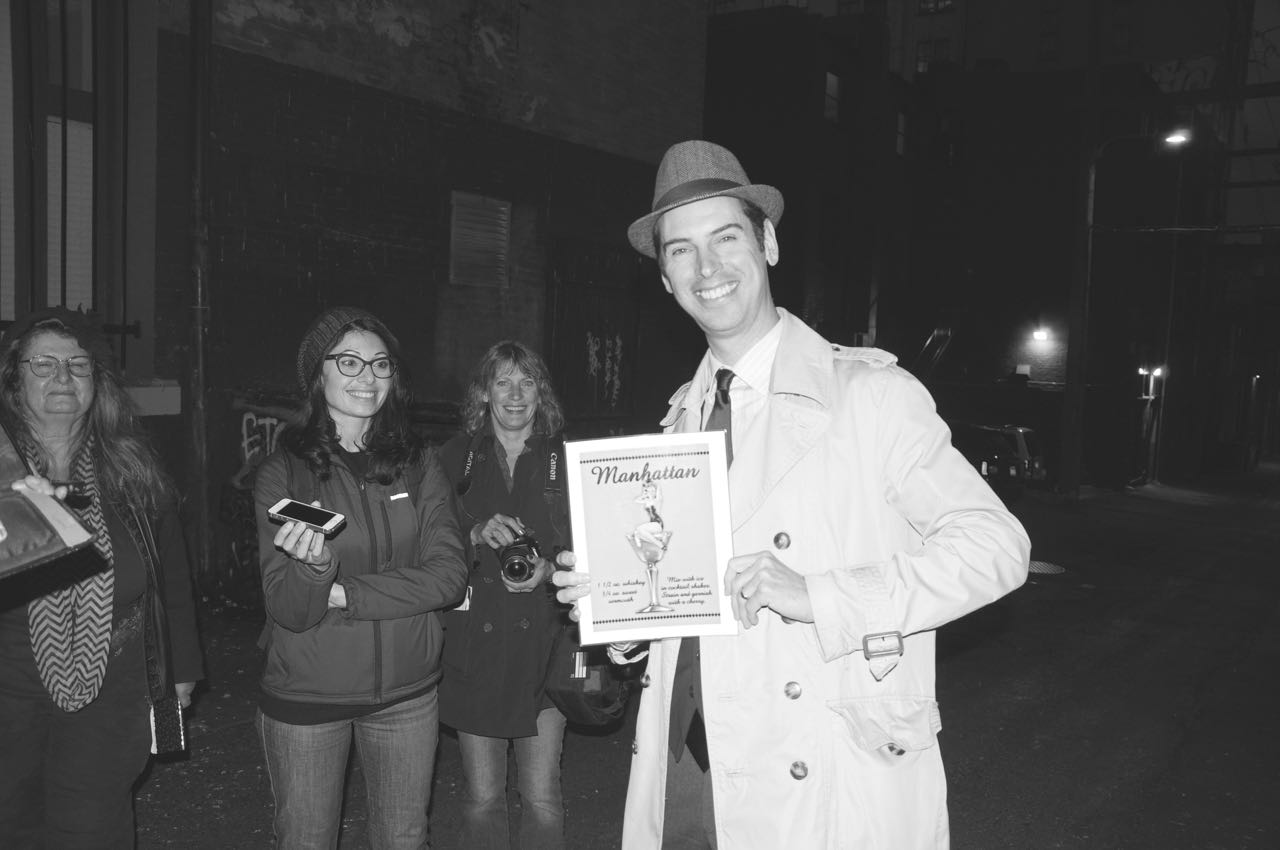

He describes how bartenders disguised poisonous liquors by drowning them in fruit juices and soda which led to the invention of the cocktail! Most famous of which was the Manhattan. Although Woods makes it sound like the Manhattan was invented here in Vancouver, which is was not, further research does document the use of Canadian whisky being used in American cocktails.

Around the corner on Pender and Beatty we stop to admire the former Sun Tower (originally the World building) to hear – over the traffic noise – the story of L.B.Taylor, a banker who fled Chicago 1897 after his bank collapsed and he was charged with embezzlement. He worked his way up the chain of the World Newspaper until he owned it, and then he lost it. So he became mayor of Vancouver, the longest running ever, with ties to organized crime. And he was a bigamist!

What a great city!

Walking past the Pint Public House, Brian K. Smith mentions how they give away free wings with a pint during happy hour on Fridays, and a burly guy standing on the sidewalk corrects him, saying the deal runs 3-6 pm from Monday-Friday. “Come on down!”

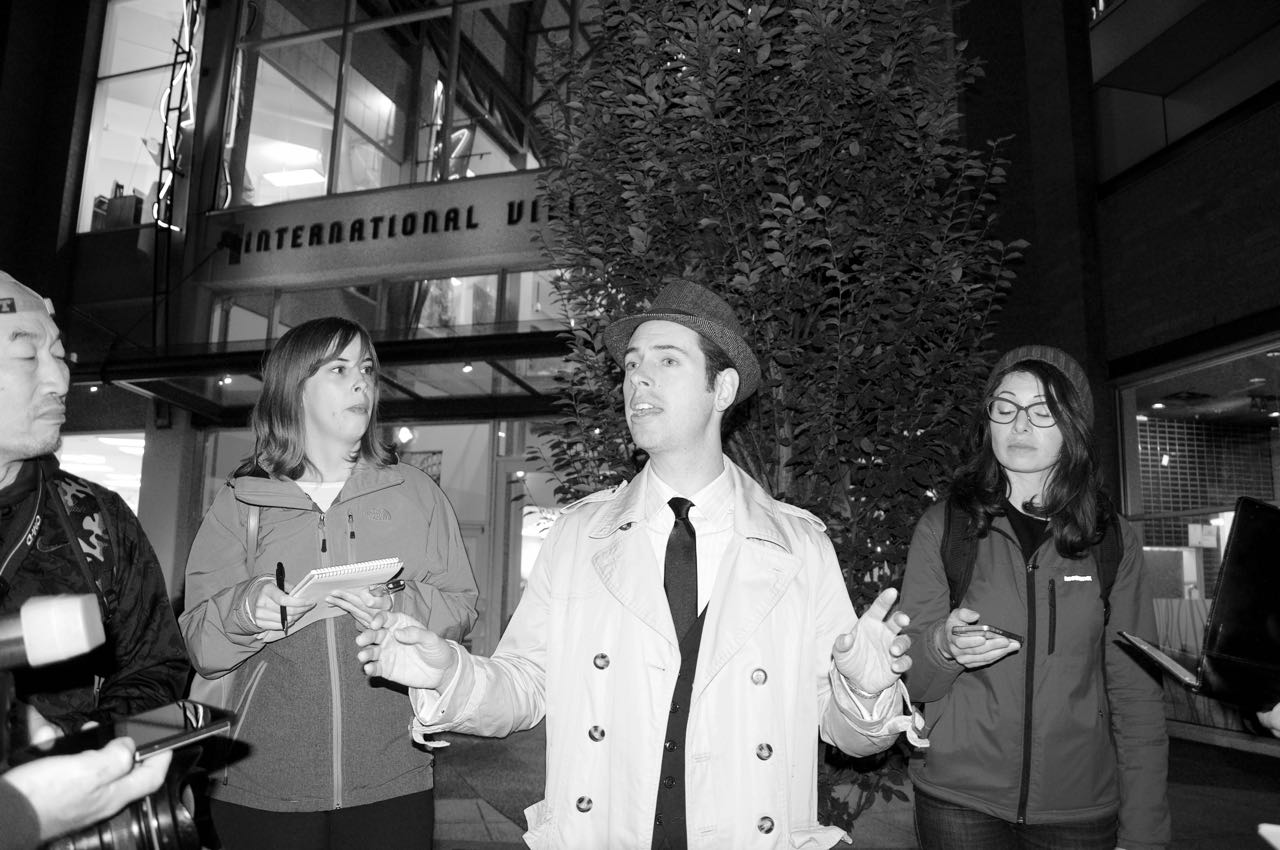

In front of the International Village, which once was the CNR train station, we find ourselves standing on old train tracks that ran through the only diagonal allyway downtown for the Inter-Urban Line from the Fraser Valley.

Here, the Prohibition story continues with the question, “What were the 3 ways to legally acquire alcohol?” Tootsie Rolls flowed as we guessed doctors, the church, and industry. We learn how the Prohibition Commissioner Walter Findley, who ran the system of distribution through pharmacies, was busted in 1919 by the Dry Squad for bootlegging confiscated liquor. He was convicted, and fined. With government corruption exposed, a repeal vote was held in 1920, in which 92,000 voters (including women!) voted against Prohibition and 55,000 in favor of keeping it.

After Repeal, we learn, you could by a permit to buy alcohol, but with the saloons still closed, there was no where to drink it except home – same as Prohibition times.

At this point I’m wishing I brought my whisky flask.

We march toward Chinatown and down Taylor Street, (yes, that Taylor) where we learn about history of Chinese immigrants who came during the 1850s gold rush and railway construction. It’s a story of overcrowding, prostitution, race riots, and deportation that makes me realize how far we’ve come.

Around the corner in Shanghai Alley we are shown a couple of old tenement buildings which housed opium dens back in the days when opium was legal. An empty lot before us once contained the King Fung Company opium factory which processed Chinese poppies and shipped opium all over Canada. Woods describes how the race riot of 1907 so damaged the King Fung factory that the owner requested compensation from the federal government for $600. The feds sent Deputy Minister of Labor William Lyon Mackenzie King to investigate the claim, and his discovery of the levels of addiction in opium dens led to his writing and the government’s passage of the Federal Opium Act of 1908.

“You can trace Canada’s 100 year war on drugs to this parking lot.” Woods concludes.

Back on Pender Street we find ourselves in front of the skinniest building in the world, the Jack Chow Insurance Company, built in 1913. The 4 foot, 11 inch wide storefront is the brightest spot on the street with vivid neon reflected in the mirrored inside walls and illuminated glass bricks glowing on the sidewalk. Just as we start to leave, strains of dramatically spooky music rise as if to invite us into a haunted house. Woods says, “That’s never happened before.”

Turning left on Carrell Street we cross Hastings and stop in an alley next to the Gospel Mission to admire the oldest ghost sign in Vancouver for the old Louvre Hotel.

At this point, Pastor Wesley Chadwick from the Gospel Mission Society steps forward with his take. He tells us that below the building is a series of catacombs through which alcohol was once smuggled. And, the whole place is infested with rats.

Everyone wants to be a tour guide!

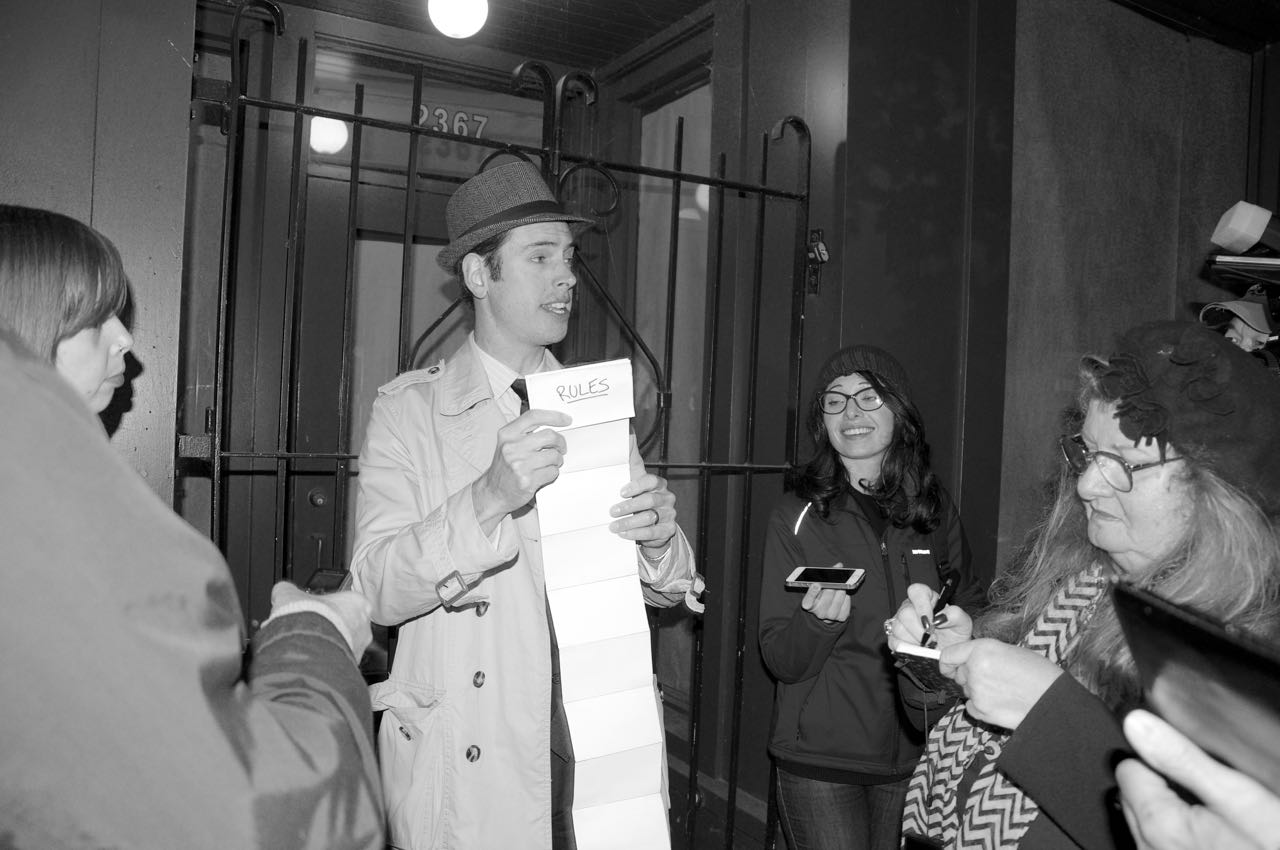

A few steps down in front of the Raleigh Hotel, we gather to hear Woods story about the new-fangled Beer Parlors, invented in 1925 to put Blind Pigs out of business.

But the Beer Parlors had rules, as Woods recited with a flourish: No standing, ordering at the bar, moving drinks around, no food, soft drinks, or cigarettes, no live or recorded music, no signs, sofas, games, cards, no more than one type of beer on sale, no service at dinnertime, and finally, no women. In 1927, women were allowed in separate fenced off areas accompanied by men.

This Raleigh Hotel featured one of the city’s first beer parlors

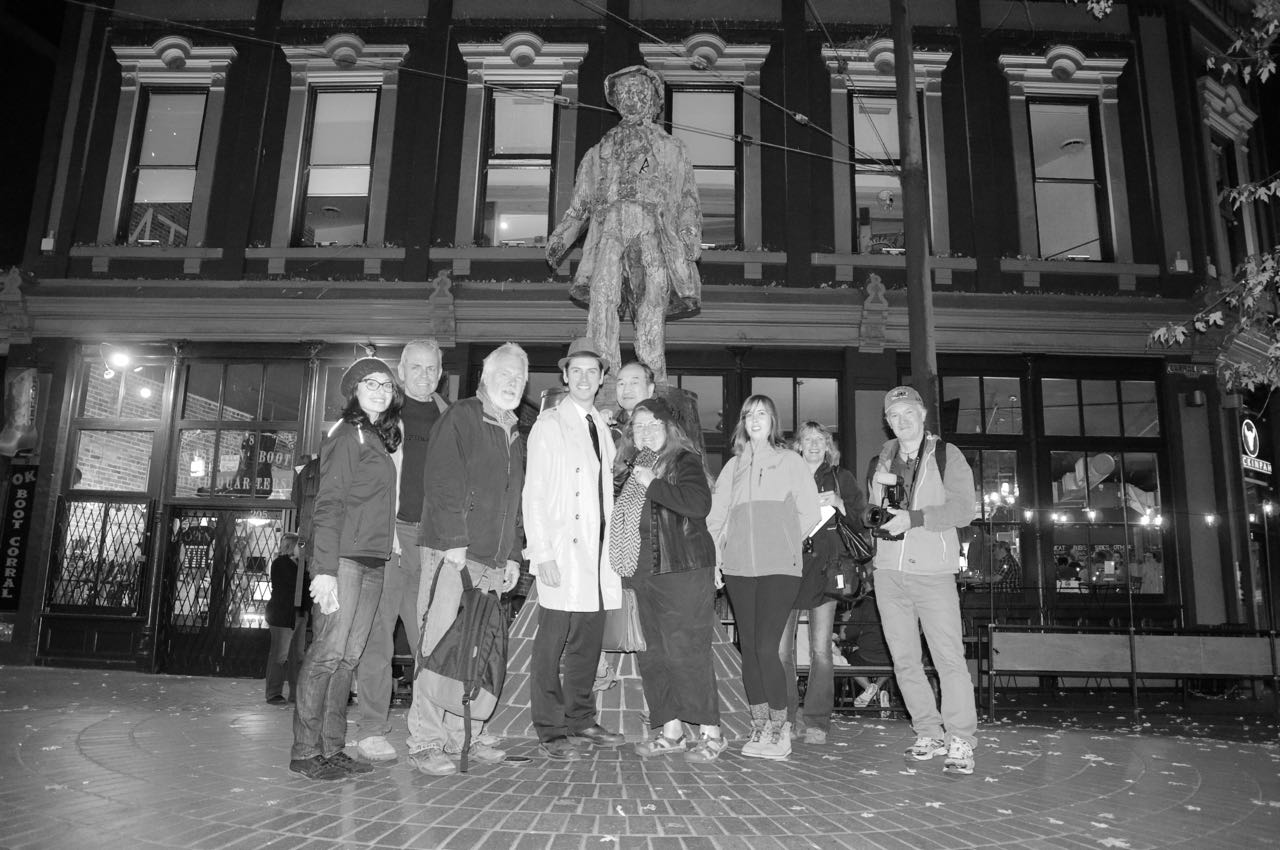

Of course, we have to stop in Maple Square to pay homage to Gassy Jack, the man who built the first saloon in Vancouver. A small disagreement ensues about how much whisky was given to the millworkers who built his bar in one day, but is forgotten as soon as we decide to take a group shot in front of Gassy Jack’s statue.

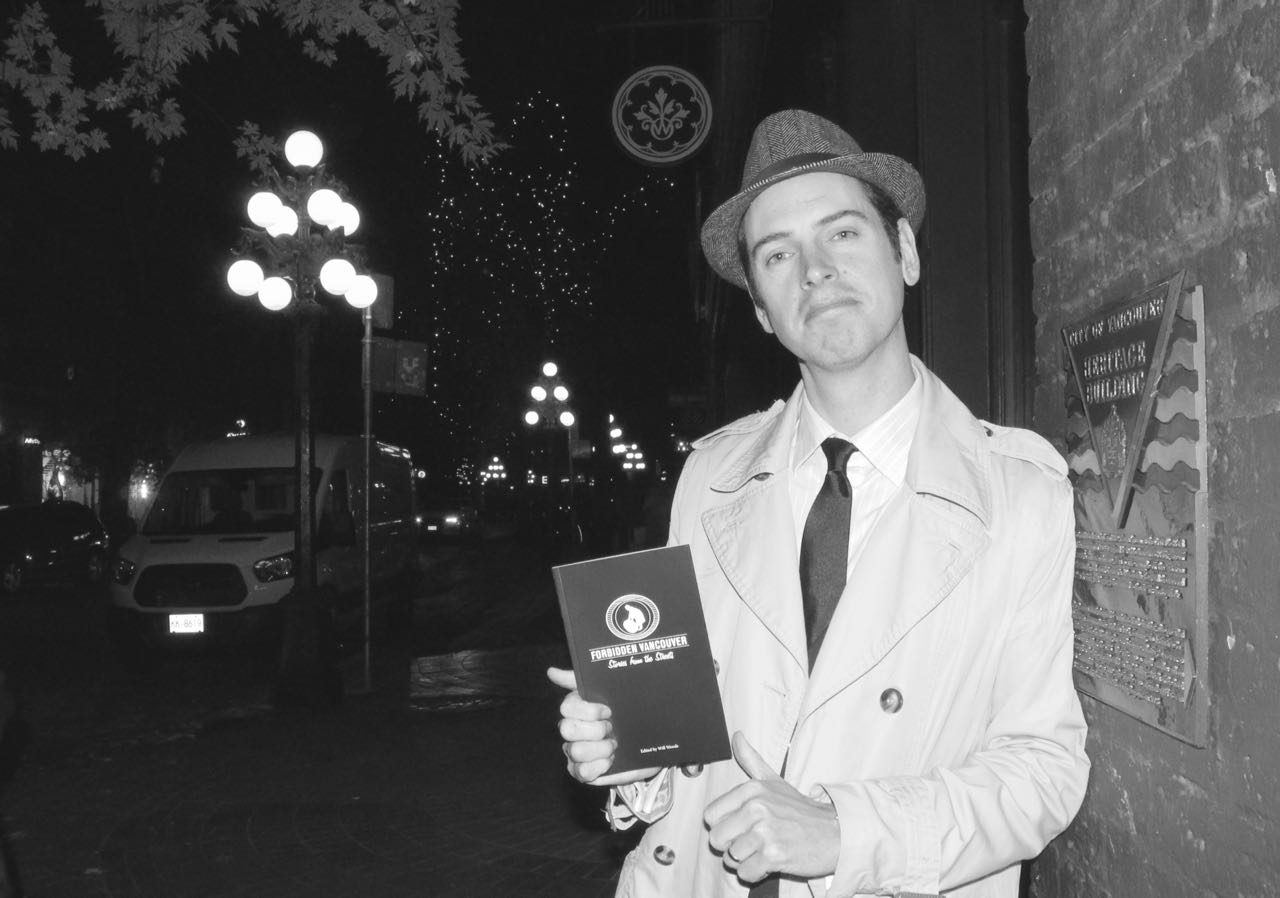

Further down Water Street, at Örling and Wu, where once was the Grand Hotel, Woods concludes the tour by reading a famous poem about Vancouver, after which he distributes copies of his book, Forbidden Vancouver: Stories from the Streets.

Then we all go for a drink. It’s the most natural way to cap the evening. At historic Steamworks brewery we cheer our host and the fun tour we enjoyed over beer – glorious, legal beer.

I appreciate it much more right now.

As well as Prohibition City, Forbidden Vancouver Tours include Secrets of the Penthouse, Lost Souls of Gastown, and the Vancouver Mysteries Game. Tickets run $20 per person, and private tours require a minimum of nine people. Tickets available through Forbidden Vancouver Tours or by phoning (604) 227-7570

This post is Mari Kane’s submission to the writing assignment for Forbidden Vancouver Tour Story Critiques, our next BCTW Meetup on November 3. All travel writers who attended the Prohibition City Tour Meetup are expected to submit stories to for critique. All story links will be posted below.

Writers, send us your story links before October 30!

No comments yet.